Media and the Vietnam War

By Alex Garcia-Kaliner

The media’s portrayal of the Vietnam war profoundly impacted both soldiers and those in the United States. Prior to the spring of 1965, fewer than two dozen journalists were reporting from Vietnam at a time. In August 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats allegedly attacked two U.S. destroyers without warning. The Gulf of Tonkin incident prompted Congress to pass the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, which gave President Lyndon B. Johnson greater authority in escalating the war. This resulted in Johnson sending 3,500 American combat troops to the South Vietnamese city of Da Nang on March 8th, 1965.

More American troops followed resulting in an increased presence of reporters. Michael Mandelbaum, the director of the American Foreign Policy program at John Hopkins University, considers the Vietnam war as the "first televised war" since television had become a more common household item in the U.S. While public opinion initially was not against the war, public opinion began to turn sour as more American troops were sent to Vietnam, and the casualties grew. On January 31st, 1968, the North Vietnamese government launched The Tet Offensive, a series of attacks carried out by the Vietcong across South Vietnam which targeted major cities (such as the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon), numerous towns, and American military installations. The offensive had three phases, which carried on until late September of 1968. While a tactical American victory, the offensive was broadcasted to the homes of American citizens. The offensive was broadcasted to the homes of American citizens, showcasing to Americans that the war was not close to being won. Combined with the increase of American casualties in Vietnam, the Tet offensive was a blow to American morale, and support for the war in the United States continued on a downward trend.

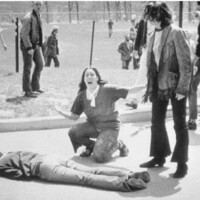

Resistance to the war in the United States increased dramatically, with public demonstrations becoming common in the American news cycle. Students at Kent State University began a demonstration on May 4th, 1970, ending with four students killed by the Ohio National Guard. John Filo, an American photographer, won the Pulitzer prize award in 1971 for his photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio screaming over the body of Jeffery Miller, one of the victims of the Kent State Shooting.

News of the Kent State Shooting spread across the nation, increasing public demonstrations and student strikes. On May 9th, over 100,000 protestors gathered outside the White House to protest the war, with other demonstrations taking place across the nation. This isn't to say however that the media's portrayal of the war at home and abroad created a unanimous consensus. A day before the protests at the White House, hard-hat construction workers in New York City attacked student demonstrators. The 1972 Presidental elections saw Nixon defeat anti-war candidate Geroge Mcgovern in a landslide victory.

Despite the polarization, dissent was ever-increasing and the United States began a withdrawal of troops after peace talks with the North Vietnamese led to the signing of the Paris Peace Accords on January 27th, 1973. The last American combat troops left Vietnam on March 29th, 1973, ending direct American involvement in the Vietnam war.